By Ethan Bakuli

Outside of the Greater Boston area or gateways cities, such as Springfield or Pittsfield, few may expect to find large numbers of black people in Massachusetts. It’s surprising, then, to hear that Florence, Mass., a village tucked in the northwest corner of the city of Northampton, had 10 percent black residents in 1850, higher than major hubs like New Bedford and Boston.

On Wednesday, Feb. 20, in light of Black History Month and in partnership with the David Ruggles Center for History and Education, the Malcolm X Cultural Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst hosted a two-part event on the impact of slavery in the Pioneer Valley.

Ruggles Center director Steve Scrimer was invited to speak at the MXCC, presenting the history of African Americans that arrived to Florence in the middle 19th century via the Underground Railroad, and quickly made the mill town their home and site of radical organizing.

The village currently known as Florence was founded in 1842, when a group of radical abolitionists decided to build a utopian community. It was first named the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, located on 500 acres of land, including a silk mill that the founding members purchased for a fifth of its original value.

Known for following the words of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, the Association believed in the immediate emancipation of enslaved peoples, supported women’s rights, practiced nonviolence and didn’t believe in electoral voting, viewing the U.S. Constitution as a pro-slavery document.

The Association quickly revamped the defunct silk mill into a worker cooperative in 1843, giving each of their members equal ownership: free and formerly enslaved black people had equal votes and full membership with whites. “There’s no place else like it that I know of in the country at the time,” said Strimer.

Black residents in Florence were capable of owning property, had equal voting rights and worked alongside white people. Almost overnight, Florence became a destination site for fugitive slaves and free blacks looking for freedom, community and employment.

Below are a few notable Florence residents that left their mark on the area:

Basil Dorsey

The Wednesday evening presentation focused on the life story of Basil Dorsey, a teamster for Florence for over three decades. Dorsey had been born into slavery in Liberty, Md., alongside his three brothers, Charles, Thomas and William. Expecting to buy his freedom after the death of their slave owner, the owner’s son ended up raising the price.

Unable to pay the outrageous cost for his emancipation, Dorsey escaped Liberty plantation and headed north. Upon arriving to New York City, Dorsey was welcomed by African American abolitionist and printer David Ruggles, who would send Dorsey up to Florence. Once settled with his family, Dorsey was employed as the village’s teamster, transporting goods as far as Albany, N.Y and Providence, R.I..

David Ruggles

Outside of his daytime job as a bookseller (he was the first African American in the nation) and grocer, David Ruggles was a member of the Vigilance Committee, an abolitionist organization tasked with raising funds to “aid colored people in distress.” Upon arriving at Ruggles’ home, formerly enslaved people were interviewed by him about their skills. From there, Ruggles would send them off to where they could find work and avoid suspicion.

“Ruggles would send people—up from New York City, up the Hudson River, up the Connecticut River, and along the coastal routes up to New Bedford—with a little bit of money and a note to the next person on the Underground Railroad,” Strimer said.

Around the same time Dorsey arrived in New York City, Ruggles assisted Frederick Douglass in arranging for his fiance Anna Murray to come up from Maryland and be married in Ruggles’ apartment. Ruggles found Douglass a job as a ships caulker in New Bedford, Mass., described in the final chapter of Douglass’ memoir.

Ruggles later arrived to Florence in 1842, escaping capture by bounty hunters who intended to enslave him (Ruggles was born free in Lyme, Conn.) After recovering from an illness, he remained in the area to practice hydrotherapy, treating patients such as William Lloyd Garrison and Sojourner Truth.

Ruggles played an integral role in the abolitionist futures of many prominent blacks, among them being Douglass, Truth and Henry Highland Garnet. Up until his passing in 1849, around 600 enslaved people were said to have escaped to freedom through Ruggles’ efforts.

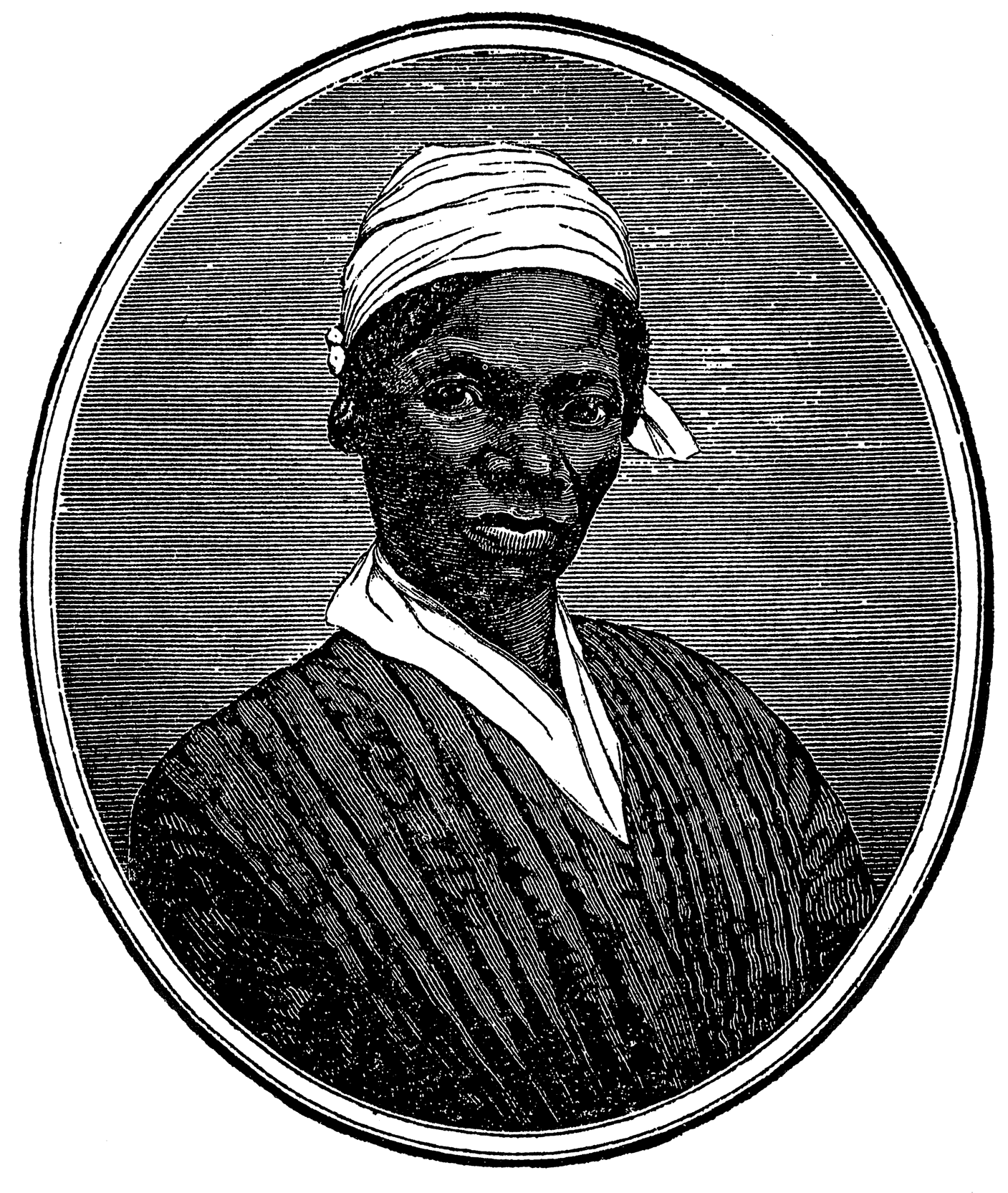

Sojourner Truth

Abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth arrived to Florence in 1844, when she joined the Northampton Association after a religious awakening. Born enslaved under the name “Isabella” in upstate New York, after escaping with her infant daughter in 1826, Truth arrived to New York City to begin a new life as a singer and preacher. On June 1, 1843, after being spoken to by God, she took her name Sojourner Truth and ventured for Western Mass.

While serving as superintendent of the laundry department of the silk mill, Truth sold pictures of herself, gave anti-slavery speeches across the country, and worked with friend Olive Gilbert, who narrated the story of her life.

In the memoriam chapter of her narrative, Truth reminisced on her life in Florence. “Very soon I found myself at Northampton talking religion and abolition all the way wherever they would hear me,” said Truth. “I was with them heart and soul for anything concerning human rights and my belief is in me yet, and cannot get out.”

The David Ruggles Center

Despite the Association’s radical mission, it didn’t last long. Four years after its beginning, the community broke up in November 1846. Immediately, local abolitionists divided portions of the land into the Bensonville Village Lots; these lots were sold at cheap prices to formerly enslaved people employed in the silk mill.

“This is very unusual,” said Strimer, referring to the historically black-owned houses still preserved in Florence. “There’s really nothing left in Springfield of the much more vibrant and larger African American community that was there at this time; [the buildings] were all wiped out in building Interstate 91 back in the 1960s.”

Many of these Village Lots remain in Florence today and can be found along the town’s African American Heritage Trail. On Saturday, Feb. 23, a group of UMass students and faculty were invited for a walking tour along the historical neighborhoods of Florence’s black residents.

“Each house that we’ve discovered has a story,” Strimer said. Over the last decade, the Ruggles Center has uncovered the forgotten history of African Americans in Florence and their contribution to the Underground Railroad and antislavery resistance. Much of that history remains in the houses previously owned by those residents.

Among the main priorities of the David Ruggles Center is preserving these houses, connecting with homeowners and developers to halt demolitions. If a home can go through “friendlier renovations” without changing its appearance, there’s a higher chance it can join the list of properties under the National Registry of Historic Places.

So far, the Ruggles Center, in collaboration with the Northampton Historical Commission and Sojourner Truth Memorial Committee, have managed to put the homes of Basil Dorsey and David Ruggles onto the National Register. But houses like Sojourner Truth’s remain on the housing market.

“It may never go on the National Register of Historic Places,” Strimer said. “Because [Truth’s house] doesn’t appear like it did in its day of historic importance. That’s sort of a big deal. They might make exceptions but I doubt it.” The Center is applying for a city grant to turn the Village Lots area into the “Florence Abolition and Equal Rights National Historic District,” ensuring the homes are protected in the future.

In the meantime, the Center hopes alliances with local institutions such as UMass will engage the public with the vibrant history of black communities in Western Mass.

“Not knowing that these people were actually in the area where I’ve been for a long time taking classes and living day to day, it was important for me to take this trip,” said Shakirah Ssebyala, senior biochemistry and molecular biology major, who previous to the tour had learned about some of the local black history in an Afro-American studies class she took.

“Being in those places helps me understand better what it was like to be them and how much they did for the community in general. I was just surprised by how much I didn’t know.”